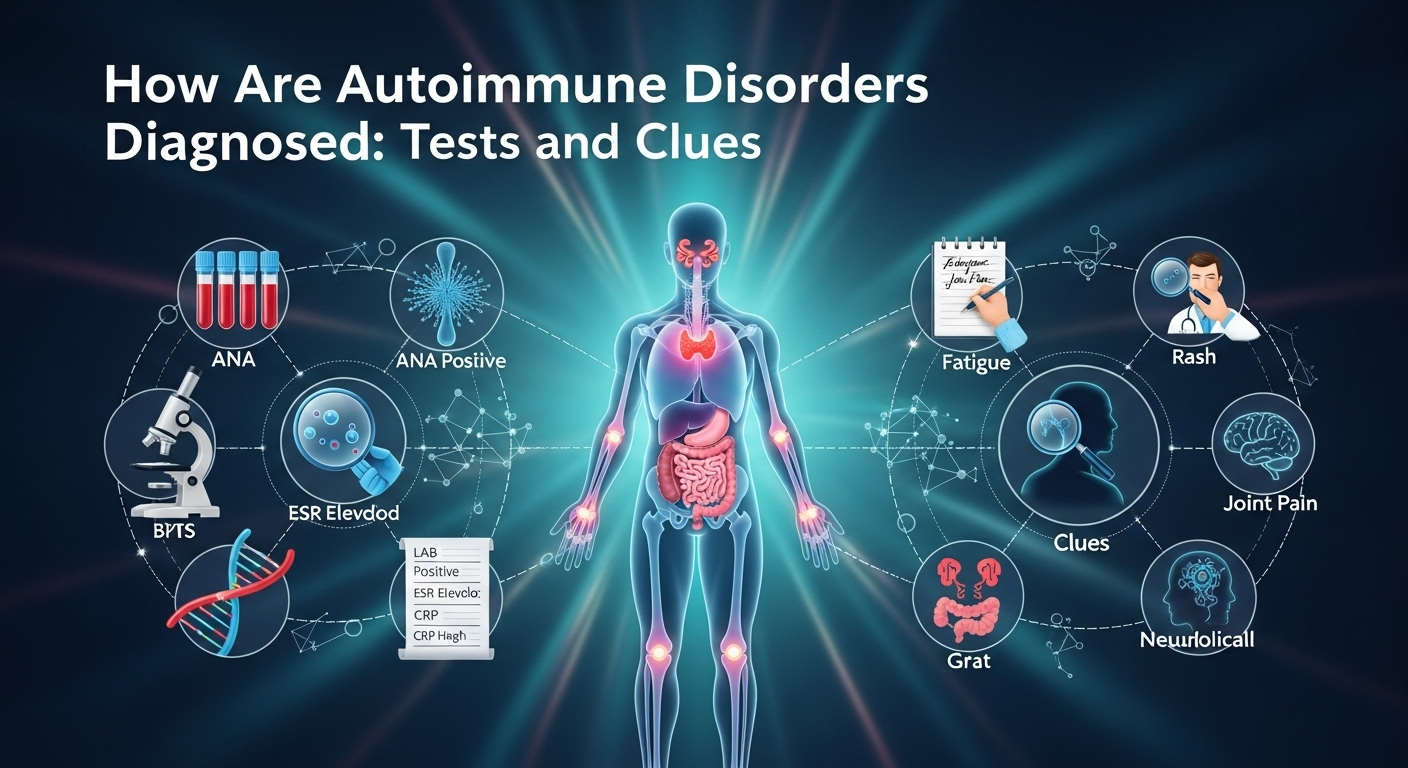

How Are Autoimmune Disorders Diagnosed: Tests and Clues

When your immune system starts attacking your own tissues, symptoms can look vague, overlapping, or even contradictory. That’s why the question many people ask—how are autoimmune disorders diagnosed—doesn’t have a one-size-fits-all answer. Instead, clinicians combine patterns from your story, exam clues, targeted labs, imaging, and sometimes biopsies. This guide walks you through that process in plain language, so you can understand the logic behind each test, what “positive” actually means, and how doctors connect the dots to arrive at a confident diagnosis.

Table of Contents

ToggleUnderstanding Autoimmune Disorders and Why Diagnosis Is Tricky

Autoimmune disorders share a common theme: immune misrecognition of self. But they do not share a single blueprint. Lupus can affect skin, joints, kidneys, brain, and blood; autoimmune thyroid disease may focus on the thyroid; celiac disease targets the small intestine; multiple sclerosis affects the central nervous system. The result is a spectrum of presentations, which can shift over time. Early in disease, you may have only fatigue and joint stiffness or rashes that come and go—clues that are easy to miss.

Complicating matters, many autoimmune tests are not black-and-white. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) test may be positive in healthy individuals, especially at low titers, while some people with bona fide autoimmune disease may test negative early on. These false positives and false negatives are why doctors never rely on a single test. Instead, they weigh probabilities, track patterns across visits, and use follow-up testing to refine the picture.

Diagnosis is also a process of exclusion. Infections, malignancies, and certain medications can mimic autoimmunity or even trigger it de novo. Because treatments for autoimmune disease often suppress the immune system, ruling out other causes first is critical. The bottom line: a correct diagnosis blends clinical judgment with targeted testing—not testing alone.

The Stepwise Diagnostic Approach Clinicians Use

The best clinicians use a stepwise algorithm that starts broad and narrows with each clue. That approach minimizes unnecessary tests and focuses on pretest probability—the chance you have a disease before testing. When the pretest probability is considered, test results are more meaningful.

Your journey often starts with a primary care clinician who orders baseline labs and looks for red flags. If an autoimmune disease is suspected, you may be referred to a rheumatologist, neurologist, gastroenterologist, endocrinologist, or dermatologist depending on which organs are mainly involved. Early, focused referrals help prevent diagnostic delay and reduce complications.

Over time, the picture may evolve. Symptoms can declare themselves more clearly, a rash might appear, or a biomarker may change. That’s why longitudinal data—notes, labs, imaging over months—is invaluable. It reveals trends and correlations that a single snapshot can’t.

1) History and Symptom Pattern Recognition

Doctors start with your story: when symptoms began, their sequence, triggers, and what helps or worsens them. Patterns matter. For example, morning stiffness lasting more than 30–60 minutes points toward inflammatory arthritis, while fatigue and an itchy rash after gluten exposure may flag celiac disease.

They also ask about family history, prior infections, and medications. Some drugs can induce lupus-like syndromes or cause a positive ANA. Travel history might suggest infections that mimic autoimmune disease. Symptom clusters—dry eyes and mouth with parotid swelling, photosensitive rashes with joint pain, or relapsing neurological deficits—helps narrow the field.

Doctors will probe systemic features: fevers, weight changes, mouth ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon, rashes, chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, neurological symptoms, and urinary changes. Each adds or subtracts probability for specific diseases. The history is the clinician’s first and most sensitive test.

2) Physical Examination: Clues on Skin, Joints, and Organs

A careful exam can be remarkably revealing. A malar “butterfly” rash suggests lupus, while silvery plaques over extensor surfaces point toward psoriasis. Nail pitting or onycholysis reinforces psoriatic arthritis suspicion. Livedo reticularis may suggest vasculitis or antiphospholipid syndrome.

Joint exams look for swelling, warmth, and tenderness with symmetrical patterns hinting at rheumatoid arthritis. Muscle strength testing can reveal proximal weakness characteristic of inflammatory myopathies. Checking glands, lymph nodes, and abdominal organs may uncover enlargement or tenderness that suggests systemic involvement.

Cardiopulmonary exams can reveal pleurisy, pericardial rubs, or rales suggesting interstitial lung disease. Neurologic exams assess reflexes, sensation, and cranial nerves—key in multiple sclerosis or peripheral neuropathies. These bedside clues guide which tests to order next and prevent shotgun testing.

3) Baseline Labs: CBC, CMP, and Inflammation Markers

Initial lab work typically includes a complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and markers of inflammation like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia can occur in lupus or as medication side effects. Elevated liver enzymes may reflect autoimmune liver disease, drug-induced injury, or viral hepatitis.

ESR and CRP are non-specific but helpful for tracking trends. Persistently high CRP suggests ongoing inflammation; however, some autoimmune diseases (like lupus) may have high ESR with normal CRP. Kidney function and urinalysis can reveal proteinuria or hematuria suggestive of glomerulonephritis, prompting further testing or biopsy.

From these basics, clinicians decide whether to proceed to autoantibody panels, imaging, or organ-specific tests. Thoughtful sequencing avoids unnecessary costs and incidental findings that can muddy the waters.

Key Blood Tests and What They Mean

Blood tests are powerful but must be interpreted in context. A “positive” result increases suspicion only if pretest probability is reasonable and the pattern fits. Conversely, a negative test doesn’t always rule out disease—especially early in the course.

A common starting point is the ANA test, which screens for antinuclear antibodies. If ANA is positive and symptoms align, doctors may order more specific extended panels (ENA) to pinpoint likely diagnoses. Disease-specific autoantibodies can dramatically elevate certainty when they align with clinical features.

It’s crucial to understand that labs differ in testing methodologies (ELISA, immunofluorescence, chemiluminescence), reference ranges, and cutoffs. Always interpret results using your lab’s standards and in conversation with your clinician.

1) ANA and ENA Panels: Interpreting Titers and Patterns

An ANA is reported as a titer (e.g., 1:80, 1:160, 1:320) and a staining pattern (homogeneous, speckled, nucleolar, centromere). Higher titers generally carry more diagnostic weight, especially ≥1:160 by immunofluorescence. Low-titer ANAs can occur in healthy people and with aging, infections, or medications.

If ANA is positive and the clinical picture fits, ENA panels test for specific extractable nuclear antigens such as anti-Smith (Sm), anti-RNP, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-SSB/La, anti-Scl-70 (topoisomerase I), and anti-centromere antibodies. These help refine diagnoses: anti-Sm is linked to lupus; anti-SSA/SSB to Sjögren’s; anti-Scl-70 to systemic sclerosis; anti-centromere to limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis.

A key nuance: ANA negativity doesn’t eliminate autoimmunity. Some diseases are often ANA-negative (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis), and a minority of lupus patients may be negative. That’s why clinical context is king.

2) Disease-Specific Autoantibodies: Adding Precision

Autoantibodies can be highly specific and prognostic:

- Anti-dsDNA: associated with lupus, particularly nephritis; levels may rise with disease activity.

- Anti-CCP (ACPA): supports rheumatoid arthritis, often more specific than rheumatoid factor (RF) and may precede symptoms by years.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): supportive but less specific; can be positive in infections and other conditions.

- Anti-GBM: indicates anti-glomerular basement membrane disease; urgent when kidney or lung hemorrhage symptoms occur.

- ANCA (PR3, MPO): supports ANCA-associated vasculitides (GPA, MPA); requires correlation with clinical features.

- Anti-TPO and anti-thyroglobulin: point to autoimmune thyroid disease; can be present in euthyroid individuals.

- Tissue transglutaminase IgA (tTG-IgA) and endomysial IgA (EMA): support celiac disease; total IgA is checked to rule out IgA deficiency.

Use of these tests should be targeted. Ordering broad panels without clinical indication increases the risk of incidental positives that do not reflect disease.

3) Complement Levels, Immunoglobulins, and Cytokines

Complement proteins C3 and C4 can be low in active immune complex diseases like lupus due to consumption. Persistently low levels may signal ongoing activity and guide treatment. Likewise, total immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) can be elevated in systemic inflammation or altered in immune dysregulation.

Advanced cytokine panels and cell-based assays are more common in research than routine practice, but the future is moving toward multi-omics signatures. For now, clinicians rely on a combination of traditional markers, clinical assessment, and selective advanced testing when results would change management.

Table: Common Autoimmune Tests at a Glance

| Test | Primary Use | Typical Positivity in Target Disease | Key Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANA (IFA) | Screening for systemic rheumatic disease | >95% in SLE; also positive in Sjögren’s, scleroderma | Low titers can be seen in healthy people; pattern and titer matter |

| Anti-dsDNA | Lupus specificity and activity | ~60–70% of SLE, correlates with nephritis | Methods vary; track with complement and urinalysis |

| ENA panel (Sm, RNP, SSA/SSB, Scl-70, centromere) | Disease refinement | Varies by antibody and disease | Interpret only if ANA-positive and symptoms fit |

| RF | RA support | ~60–80% in RA | False positives in infections, older age |

| Anti-CCP (ACPA) | RA specificity | ~60–80% in RA; high specificity | Can be positive before symptoms |

| ANCA (PR3/MPO) | Vasculitis support | ~80–90% in GPA/MPA | Drug-induced ANCA exists; correlate clinically |

| Anti-TPO | Autoimmune thyroid disease | >80–90% in Hashimoto’s | May be present in normal thyroid function |

| tTG-IgA/EMA | Celiac disease | High sensitivity/specificity | Check total IgA; biopsy for confirmation |

| Complement (C3/C4) | Activity marker in SLE | Often low during flares | Also low in severe infections or liver disease |

| HLA-B27 | Spondyloarthritis risk marker | Present in many with axial SpA | Also present in healthy carriers; not diagnostic alone |

Note: Ranges and associations vary by population and laboratory methodology; interpret within the full clinical context.

Imaging, Functional Tests, and Biopsies

Blood tests are only part of the picture. When autoimmunity affects organs or structure, imaging and functional tests can reveal patterns invisible to lab work. For instance, X-rays of hands in rheumatoid arthritis may show erosions, while MRI detects inflammation early—before permanent damage.

Biopsies provide tissue-level confirmation and can be decisive when the diagnosis remains uncertain. A skin biopsy for vasculitis or a kidney biopsy in lupus can change treatment strategy immediately, steering therapy away from guesswork and toward targeted intervention.

The timing of these tests is important. Over-imaging too early may yield incidental findings, while delayed imaging risks irreversible damage. Clinicians choose modalities that answer specific clinical questions.

1) Ultrasound, X-ray, MRI: When Pictures Speak

Musculoskeletal ultrasound can detect synovitis, tenosynovitis, and erosions in real time, without radiation. It’s useful in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis to document active inflammation and guide joint injections.

Plain X-rays remain valuable for detecting bone erosions, joint space narrowing, and sacroiliitis in spondyloarthritis. MRI shines in early disease, revealing bone marrow edema, enthesitis, and soft tissue changes before damage occurs. In central nervous system autoimmunity, MRI is critical for detecting demyelinating lesions in multiple sclerosis.

The choice of modality depends on the suspected disease and the question at hand: Is there inflammation? Is there damage? Answering both guides urgency and treatment.

2) Organ-Specific Tests: Breathing, Heart, Nerves, and Gut

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) evaluate for interstitial lung disease or airway involvement, often seen in systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or myositis. An echocardiogram can look for pericardial effusion or pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis.

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography help clarify peripheral neuropathies or myopathies—critical in vasculitic neuropathy or inflammatory myositis. In gastrointestinal autoimmunity, endoscopy with biopsies supports celiac disease or autoimmune gastritis. Targeted organ testing turns suspicion into evidence.

These tests also monitor progression. For example, declining diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) on PFTs may signal worsening interstitial lung disease, prompting treatment escalation.

3) Biopsy and Histopathology: The Gold Standards

When blood tests and imaging suggest autoimmune involvement but uncertainty remains, biopsy offers definitive proof. Kidney biopsies classify lupus nephritis, directly informing therapy. Temporal artery biopsies confirm giant cell arteritis; skin biopsies can identify small-vessel vasculitis; minor salivary gland biopsy supports Sjögren’s syndrome.

Pathologists look for characteristic patterns: immune complex deposition, granulomas, vasculitic changes, or lymphocytic infiltrates. Even when an autoimmune disease is suspected clinically, tissue confirmation may be necessary before starting potentially toxic immunosuppression. Biopsies transform guesswork into clarity.

Differential Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis Pitfalls

Autoimmune diseases often masquerade as other conditions—and vice versa. Any diagnostic pathway must rule out mimics to avoid harmful treatments. A disciplined differential diagnosis reduces error and improves outcomes.

Infections, malignancies, and drug reactions can mimic or trigger autoimmune phenomena. A positive autoantibody should not eclipse clinical judgment. The reliability of a test depends on the patient in front of you, not an abstract lab report.

Clinicians remain alert for overlap syndromes, where more than one autoimmune disease coexists. They also consider seronegative disease—patients with classic symptoms but negative standard tests—because immune dysregulation doesn’t always follow textbook patterns.

1) Infections, Malignancy, and Drug-Induced Autoimmunity

Chronic infections (hepatitis B/C, tuberculosis, HIV) can present with systemic symptoms and positive autoantibodies. Treating with immunosuppressants before excluding these can be dangerous. Similarly, subacute bacterial endocarditis can mimic vasculitis, complete with positive ANCA.

Malignancies can present with paraneoplastic syndromes—autoimmune-like phenomena driven by the immune response to cancer. Weight loss, night sweats, or unusual lab patterns may trigger cancer screening. Certain medications (hydralazine, procainamide, TNF inhibitors) can cause drug-induced lupus or ANCA positivity.

A thorough medication and exposure history is essential. Stopping the culprit drug can lead to symptom resolution, sparing unnecessary long-term therapy.

2) Overlap Syndromes and Seronegative Disease

Overlap syndromes, such as mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) or rhupus (RA-lupus overlap), combine features of multiple autoimmune disorders. These require flexible diagnostic thinking and tailored treatment plans.

Seronegative forms exist across conditions: seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, ANA-negative lupus, seronegative spondyloarthritis. Imaging, biopsy, and longitudinal observation become even more important in these cases. Don’t let a negative blood test overshadow convincing clinical evidence.

3) Red Flags That Warrant Urgent Referral

Certain symptoms demand prompt specialty evaluation:

- New severe headache with scalp tenderness or jaw pain in adults over 50 (possible giant cell arteritis)

- Rapidly worsening kidney function with blood/protein in urine (possible vasculitis or lupus nephritis)

- Hemoptysis with anemia (possible pulmonary-renal syndrome)

- Progressive weakness with difficulty climbing stairs or lifting arms, especially with rash (possible inflammatory myopathy)

- Visual loss or double vision with neurological deficits (possible demyelination)

These scenarios can threaten organs or life and may require urgent steroids or expedited diagnostics, sometimes including inpatient care.

Monitoring, Activity Scores, and When to Re-test

Diagnosis isn’t the endpoint—it’s the start of ongoing assessment. Autoimmune diseases fluctuate; you and your clinician need objective ways to track activity, adjust therapy, and catch complications early. Monitoring also ensures treatments are working and not causing harm.

Not all tests need repeating. Some autoantibodies remain stable regardless of activity, while others track disease. Knowing the difference avoids unnecessary blood draws and anxiety over meaningless changes.

The art is balancing evidence with the patient’s lived experience: energy levels, pain, function, and quality of life. Both objective and subjective measures matter.

1) Disease Activity Indices and Scores

Clinicians use validated tools:

- DAS28 or CDAI for rheumatoid arthritis to quantify joint counts, inflammation markers, and patient assessment.

- SLEDAI or BILAG for lupus to capture multi-organ involvement.

- ESSDAI for systemic activity in Sjögren’s.

- Mayo endoscopic score for inflammatory bowel disease.

- EDSS for multiple sclerosis disability.

These algorithms translate complex clinical pictures into trackable numbers, guiding escalation or de-escalation of therapy and establishing treat-to-target strategies.

2) Biomarkers Over Time: What Changes Matter

CRP and ESR are useful for many conditions, but in lupus, complement levels and anti-dsDNA trends can be more informative. In RA, anti-CCP status doesn’t fluctuate much, but CRP and joint counts do. In celiac disease, tTG-IgA levels typically fall with a strict gluten-free diet, indicating mucosal healing.

Re-testing strategy:

- Repeat tests that reflect activity (CRP, ESR, complement, anti-dsDNA, urinalysis for protein/hematuria).

- Avoid repeating stable diagnostic antibodies unless there’s a compelling reason.

- Re-image when symptoms change or to monitor known organ involvement.

3) Personalized Medicine: Genetics, HLA, and Multi-omics

Genetic markers like HLA-B27 increase risk for spondyloarthritis; HLA-DRB1 “shared epitope” alleles are linked to RA severity; and specific HLA variants influence celiac disease risk. These markers are risk indicators, not definitive diagnostics, and are interpreted alongside clinical evidence.

The future is moving toward multi-omics (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) and machine learning models that integrate symptoms, labs, imaging, and digital biomarkers. While promising, these are supplementary for now. Clinical reasoning remains the raison d’être of accurate diagnosis.

Patient Preparation and Smart Questions to Ask Your Doctor

You play a central role in your own diagnostic journey. Preparing for appointments, organizing your health data, and asking targeted questions can streamline the process and reduce delays.

Bring a clear symptom timeline, list medications and supplements, and note what triggers or relieves symptoms. Photos of rashes, swelling episodes, or Raynaud’s color changes on your phone can be invaluable. Wear comfortable clothing for a full exam and consider bringing a support person to help you remember details.

Understanding what each test can and cannot tell you reduces anxiety. Ask how results will change the plan, what false positives mean, and whether additional testing is needed or can wait. This partnership fosters shared decision-making.

1) Preparing for the Appointment

- Keep a concise diary: onset, duration, severity, and patterns of symptoms.

- List family history of autoimmune diseases, thyroid problems, celiac disease, or psoriasis.

- Include vaccination and infection history; note any recent new medications.

Organize prior labs, imaging, and specialist notes. If you’ve had an ANA or other autoantibody test in the past, bring the exact titer and pattern. Consistency in labs aids interpretation; switching methods midstream can blur trends.

2) Interpreting Results and Next Steps

Ask:

- “What is the pretest probability that I have X disease, and how does this test change it?”

- “If this result is positive, what would we do differently? If negative, what’s next?”

- “Which results reflect activity versus risk versus diagnosis?”

- “Is a biopsy or imaging study likely to change management?”

Clarify timelines and follow-ups. Autoimmunity often unfolds over months; a watchful waiting approach with targeted testing can avoid overdiagnosis while keeping you safe.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I have an autoimmune disease with normal blood tests?

A: Yes. Some conditions are seronegative, and early disease may not show classic markers. Doctors rely on clinical evidence, imaging, and sometimes biopsy. Reassessment over time is common.

Q: Is a positive ANA enough to diagnose lupus?

A: No. ANA is a screening test. Diagnosis requires compatible clinical features and, often, more specific antibodies or organ involvement. Many healthy people can have a low-titer positive ANA.

Q: Which doctor should I see first?

A: Start with your primary care clinician. Depending on symptoms, they may refer you to a rheumatologist, endocrinologist, neurologist, gastroenterologist, or dermatologist.

Q: How long does diagnosis take?

A: It varies. Straightforward cases may be diagnosed in weeks; complex or evolving cases can take months. Tracking symptoms and test trends accelerates clarity.

Q: Will diet or lifestyle changes help diagnosis?

A: While lifestyle changes can improve symptoms and overall health, diagnosis hinges on clinical and laboratory evidence. Keep your clinician informed of any major changes (e.g., gluten elimination) as they can affect test interpretation.

Q: Are genetic tests definitive for autoimmune disease?

A: No. Genes like HLA-B27 increase risk but are not diagnostic on their own. They are pieces of a larger puzzle.

Q: Can infections trigger autoimmune flares?

A: Yes. Infections can both mimic and trigger flares. It’s critical to distinguish between the two before escalating immunosuppression.

Conclusion

Answering “How are autoimmune disorders diagnosed?” requires zooming out and in—seeing the whole person, then focusing on precise clues. The process blends:

- Careful history and exam

- Baseline labs and targeted autoantibody testing

- Imaging and organ-specific functional tests

- Biopsies when uncertainty remains

- Ongoing monitoring with activity scores and selected biomarkers

No single test defines autoimmunity universally. Instead, patterns over time drive the most accurate diagnoses and safest treatments. Partner with your clinician, ask focused questions, and understand what each test contributes—and what it doesn’t. With a methodical approach, the path from symptoms to clear diagnosis becomes navigable and, most importantly, actionable.

Short summary (English):

Autoimmune disorders are diagnosed through a stepwise, pattern-based approach that combines history, physical exam, baseline labs, and targeted autoantibody tests with imaging, organ-specific studies, and sometimes biopsies. Because many tests have false positives or negatives, clinicians interpret results in context using pretest probability and disease activity scores. Monitoring focuses on meaningful biomarkers and clinical indices, while differential diagnosis rules out infections, malignancies, and drug-induced mimics. Patients can speed clarity by documenting symptom patterns, organizing prior results, and asking how each test changes management.